We’ve seen literary writers dip their toes into genre recently, and it really shouldn’t be a surprise. Genre has actually been tempting literary writers since publishing began—and even before, if you consider that all religions have origin stories involving the supernatural. I thought I was a literary writer for a long time, and before I discovered my own route to speculative writing, I found my favored geography in books that were considered literary, but actually belonged in genre. These are portal books in a way, because they stand at the doorway between realistic and speculative.

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll

For me, this book is the source of all the delights that result from a change in perspective, and also a certain kind of heroine, resourceful, adaptive and practical. This is my go-to book, the lodestar for dealing with the fantastic on an everyday basis. It takes the familiar and enjoys it, which is what we should do with reality—examine it, approach it, question it and appreciate it. Like everyone else, I suspect, the things that have influenced me the most were the Eat Me/Drink Me episode and the later book, Through the Looking Glass. I find myself writing a number of stories about the world behind the glass, and each one owes royalties to Alice. But it was the fun in this world that helped me shape how, at least occasionally, the strange and problematic are doorways to fun.

For me, this book is the source of all the delights that result from a change in perspective, and also a certain kind of heroine, resourceful, adaptive and practical. This is my go-to book, the lodestar for dealing with the fantastic on an everyday basis. It takes the familiar and enjoys it, which is what we should do with reality—examine it, approach it, question it and appreciate it. Like everyone else, I suspect, the things that have influenced me the most were the Eat Me/Drink Me episode and the later book, Through the Looking Glass. I find myself writing a number of stories about the world behind the glass, and each one owes royalties to Alice. But it was the fun in this world that helped me shape how, at least occasionally, the strange and problematic are doorways to fun.

The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat by Oliver Sacks

It’s odd to have a non-fiction book on a list about fiction influences, but this book is a rarity, an exploration of the anomalies of the mind. As we all probably know, different locations in the brain control different functions—not only physical functions, but cognitive ones as well. And when your brain ceases to understand the difference between a face and a hat, then we are indeed in alien/speculative territory. Sacks approached his patients with humanity and respect, and he suggests, to me, that we can approach the perturbations of reality with kindness rather than cruelty. Fascinating and indeed terrifying.

It’s odd to have a non-fiction book on a list about fiction influences, but this book is a rarity, an exploration of the anomalies of the mind. As we all probably know, different locations in the brain control different functions—not only physical functions, but cognitive ones as well. And when your brain ceases to understand the difference between a face and a hat, then we are indeed in alien/speculative territory. Sacks approached his patients with humanity and respect, and he suggests, to me, that we can approach the perturbations of reality with kindness rather than cruelty. Fascinating and indeed terrifying.

The Chess Garden by Brooks Hansen

Ostensibly a story about a doctor who went off to the Boer War and wrote back to his family describing what he saw, it amounts to a fantastic journey to a land where the Platonic ideals of things exist, and where if you destroy the original spoon, then spoons themselves cease to have any meaning. In fact, the journey is about enlightenment and death. The stories that are important to me are, indeed, all about journeys, whether interior or exterior, and the best ones unite these aspects. The Platonic spoon, the ability to destroy the idea of an object, has stayed with me a long time. We understand things only on the basis of the ideas we have about them. Give me something out of context and what will I do with it? Take away context, that’s what interests me. There’s a one- or two-page scene in this book where someone opens up the spigot of darkness, and can’t turn it off. Journeys in fantastic fiction turn the obstacles into metaphors, and in many cases, the goal as well.

Ostensibly a story about a doctor who went off to the Boer War and wrote back to his family describing what he saw, it amounts to a fantastic journey to a land where the Platonic ideals of things exist, and where if you destroy the original spoon, then spoons themselves cease to have any meaning. In fact, the journey is about enlightenment and death. The stories that are important to me are, indeed, all about journeys, whether interior or exterior, and the best ones unite these aspects. The Platonic spoon, the ability to destroy the idea of an object, has stayed with me a long time. We understand things only on the basis of the ideas we have about them. Give me something out of context and what will I do with it? Take away context, that’s what interests me. There’s a one- or two-page scene in this book where someone opens up the spigot of darkness, and can’t turn it off. Journeys in fantastic fiction turn the obstacles into metaphors, and in many cases, the goal as well.

The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov

I named my first cat after Behemoth, the cat that walks around Moscow with the devil. And one small detail—that the devil wears plaid—never ceases to delight me. No one credible wears plaid. This is a wild romp of a book, highly political but decidedly enjoyable even if you’re not familiar with the politics of 1920s Russia. A good story reflects the society it came from, but a great story challenges it. And when Margarita finally gets the courage to ride a broom over Moscow, my heart soars with her. But I also see that, when playing against the devil, it’s very easy to get in over one’s head.

I named my first cat after Behemoth, the cat that walks around Moscow with the devil. And one small detail—that the devil wears plaid—never ceases to delight me. No one credible wears plaid. This is a wild romp of a book, highly political but decidedly enjoyable even if you’re not familiar with the politics of 1920s Russia. A good story reflects the society it came from, but a great story challenges it. And when Margarita finally gets the courage to ride a broom over Moscow, my heart soars with her. But I also see that, when playing against the devil, it’s very easy to get in over one’s head.

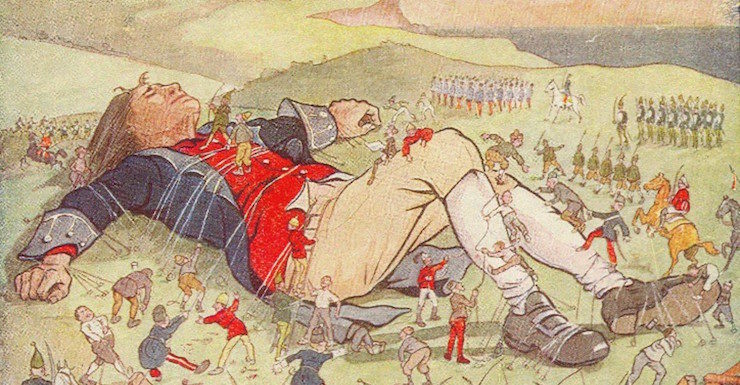

Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift

In the 18th century some travel books were entirely made up by authors who never actually went on their fabled journey, travel being as arduous as it was. People were—and still are—delighted to believe just about anything when it comes to strangers. Travel is an unparalleled opportunity to champion one’s own personal beliefs about politics, race, class, gender, and cultural irregularities, and to give instances of the mindless rituals of people who are not like us. There is no greater sense of superiority than that of noting how every other society can be improved. They will never see the errors of their ways if we don’t point it out to them.

In the 18th century some travel books were entirely made up by authors who never actually went on their fabled journey, travel being as arduous as it was. People were—and still are—delighted to believe just about anything when it comes to strangers. Travel is an unparalleled opportunity to champion one’s own personal beliefs about politics, race, class, gender, and cultural irregularities, and to give instances of the mindless rituals of people who are not like us. There is no greater sense of superiority than that of noting how every other society can be improved. They will never see the errors of their ways if we don’t point it out to them.

Karen Heuler’s stories have appeared in over 100 literary and speculative magazines and anthologies, from Alaska Quarterly Review to Clarkesworld to Weird Tales. She has published four novels and three story collections with university and small presses, and a recent collection was chosen for Publishers Weekly’s Best Books of 2013 list. She has received an O. Henry award, been shortlisted for a Pushcart prize, for the Iowa short fiction award, the Bellwether award, and twice for the Shirley Jackson award for short fiction. Aqueduct Press has just published her novella, In Search of Lost Time, about a woman who can steal time. Find her at karenheuler.com, befriend her at /karenheuler on FB, or follow her on Twitter (@karenheuler), which she neglects shamefully.

Karen Heuler’s stories have appeared in over 100 literary and speculative magazines and anthologies, from Alaska Quarterly Review to Clarkesworld to Weird Tales. She has published four novels and three story collections with university and small presses, and a recent collection was chosen for Publishers Weekly’s Best Books of 2013 list. She has received an O. Henry award, been shortlisted for a Pushcart prize, for the Iowa short fiction award, the Bellwether award, and twice for the Shirley Jackson award for short fiction. Aqueduct Press has just published her novella, In Search of Lost Time, about a woman who can steal time. Find her at karenheuler.com, befriend her at /karenheuler on FB, or follow her on Twitter (@karenheuler), which she neglects shamefully.